Take THREE at writing this up. (Ecto, you are dead to me. It is not

worth my time to ask for a refund, that’s just how dead to me you are.)

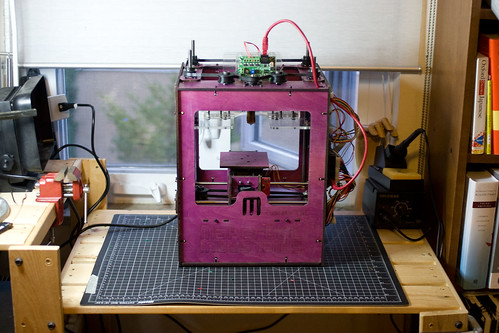

If you’re considering a MakerBot Cupcake or other scratchbuilt,

open-source 3D printer for your home, read on. I’ve had one for several

weeks now and this is yet another entry about life with a first-gen,

home-scale 3D printer.

Location

It’s noisy. It smells. It’s like having a

mimeograph in your house. Yes, you can do a lot of useful things with

it and yes, it will generate a number of new and interesting smells and

sounds.

When I first set mine up, I had it on a hardwood floor in my

second-floor studio. While it was printing, I walked down stairs and

discovered it was about as loud downstairs as upstairs thanks to all the

vibrations being transmitted through the floor. I’ve since moved it to

the top of some shelves and will also add a rubber sheet under it to see

how that helps with the noise.

The steppers are noisy. Printing means that at least one, and often two going at the same time. How noisy are steppers? Well, people have performed songs using steppers, that’s how noisy they are.

Finally there’s the lovely smell of melting ABS. The MSDS for ABS isn’t

too terrifying, but I get tired of the smell after awhile. Plan on

having your MakerBot near a source of fresh air or other ventilation.

Oh, and solve all these location issues while keeping it next to the

computer you’re using to drive it, as you’ll be going between the two

quite a bit for the first few weeks.

Tools

There are a few tools that I’ve found handy to keep near the MakerBot. Handy enough that I’m buying “replacements” for where they used to live, because I’m tried of moving them back and

forth.

- dykes or wire cutters: useful for getting a nice clean cut on the ABS filament single-edge

- razor scraper: if you’re using acrylic platforms, this makes it much easier to get the raft off.

- small (~15cm) ruler for adjusting/aligning the Z-axis after you crash the head.

Software

I’m focused on OSX right now, but some of these packages are available on those platforms and may have different issues.

The biggest issue I’m facing on OSX is Intel vs. PowerPC. It seems that the python builds for these two platforms aren’t “bug compatible” across the two different architectures. Skeinforge, the primary tool used by the greater reprap community for converting STL to g code functions differently on the different architectures. My plan had been to dedicate my old PowerPC G5 to running the MakerBot and some scanners, but currently I have to keep my Intel MacBook nearby in order to run skeinforge.

One of the handier tools if you’re using OSX is

Other than that, things have been going fairly well. Blender turns out to be very powerful, but it’s not only non-intuitive, it’s counter-intuitive in places. Do a bunch of the tutorials and get used to the idea that a “unit” in Blender is “1mm” on the printer.

Printing

Almost every problem I had was due to not getting the extruder to the right temperature for ABS. The supplier changed parts on the MakerBot crew and nobody noticed until too late, so some of us got “the tiny thermistor” (about 1mm wide) that reads higher than the normal thermistor people were using. After some fiddling around with a temperature probe, I made a new source file for the build, you can find it on the makerbot group.

Once I nailed the temperature, it was time to do something about alignment/adjustment. I tightened the belts as snug as possible then trammed my build platform (more on that in a future post). The final step will be to go to a heated platform, as this seems to yield large prints that don’t warp.

[tags]makerbot,reprap[/tags]